The Customer isn't Always Right - The Importance of being an Attractive Client

- Mar 6, 2018

- 4 min read

With firms in many industries returning to their core capabilities and being increasingly selective when taking on projects, the time has come for buying organisations to lose the complacency and consider things from a supplier's perspective.

So you work for a big company. A global brand. FTSE 100 perhaps. Maybe the leading firm in the sector. Suppliers will be tripping over each other to provide you with their most proactive account managers, their most skilled engineers, their slickest service and all at the keenest possible cost, right?

Wrong. Well maybe. But the days of the 'pull of the brand' are numbered.

There may be some 'kudos' attached to securing a major player or premium brand as a client for a supplier seeking to establish itself within an industry. Yet mainstream suppliers are ceasing to put a value on being associated with those customers perceived as prestigious and shifting their focus to those who present a genuinely alluring prospect when it comes to forging a lasting commercial relationship.

Leading procurement professionals are beginning to recognise the winds of change and sail with them rather than swim against the tide. We examine the methods they are employing to elevate their corporate shelf-appeal.

Put the boot on the other foot

Just as buying organisations routinely segment their suppliers, supply side firms complete this exercise mutatis mutandis.

By stepping into their shoes and mapping how suppliers perceive a firm, the first step is taken in determining how to best manage those relationships and how accommodating one should be. This is achieved by clarifying the context of our significance to the supplier - and therefore the relationship - within the market as a whole.

By far the simplest method of profiling these views is using the Supplier Preference Model.

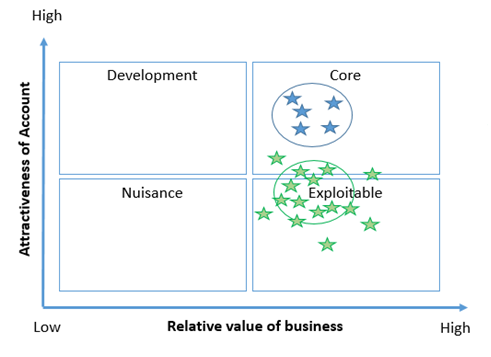

The model has been seen in various guises but most commonly plots the relative value of business on offer to the supplier against the general attractiveness of the account.

In the example shown above, two types of suppliers have been plotted within one supply area - for example distributors and manufacturers who will supply directly. It can be seen at a glance that one type perceive the company as a core client whereas the other see it as an opportunity to supply at their highest possible margin.

Understanding Why

There are a plethora of factors that can be taken into account to understand why a firm exhibits the level of attraction it does. It pays, however, to focus on effecting the most change across the most critical areas of the supply base.

The single most powerful factor comes in the form of 'Relative Value of Business' or volume. It won't be news to any buyer that finding ways to consolidate their purchases is the primary method of making their sourcing project attractive to the market. Whilst somewhat obvious, this isn't always simple, especially in project driven sectors or those with volatile demands.

Where accurate forecasting is available, consolidating volumes without compromising on security of supply should lead to offering a more attractive proposition for the marketplace, and hence better prices, conditions, quality and responsiveness.

The other factors require more consideration and often a more subtle and varied approach.

Consider what is important to your suppliers: is it a long term contract? Shortened payment terms? Adherence to those terms?

Is it an open working relationship? Sharing of risk and innovation? A detailed and consistent specification?

A common issue for those larger corporations is to impose particular contract forms, terms and conditions on their supply base on a blanket basis.

Whilst the intentions here are often entirely reasonable - standardising should lead to more consistency and less burden in contract management as well as averting certain risks - this often puts off or in some cases totally excludes suppliers from the marketplace.

A good example of this is model contract forms, such as NEC3 or JCT within the construction industry. Intended to create consistency and apply a common approach across the sector, many engineering buying organisations attempt to apply the contracts to a wide variety of purchases. Smaller firms from outside the industry may lack the skills or resources available to agree and manage these contracts, leading to a few 'major players' subcontracting works and ultimately project managing an interface with the end user.

Another frequent oversight is the application of one-sided terms in purchase agreements, such as application of Intellectual Property Rights.

A key clause in any modern contract, IPR can often be contentious in projects where an asset or solution is delivered and installed. Well-meaning company solicitors will often attempt to ensure that the buying organisation retains ownership of any IPR generated by collaborative projects with suppliers. Unfortunately this often prevents that marketplace from sharing its greatest ideas and innovations.

A good alternative would be to draft an IPR provision that protects the rights of the parties’ technical information to remain their own. This would enable visibility and use of protected IP via the granting of licenses for use in connection with the projects for as long as is necessary. This mitigates any risk of use of the IP by the other party on other projects.

It may also be appropriate to seek an indemnity from the supplier in instances where the supplier’s IPR that is being used under licence infringes the rights of existing IP.

Opening up: When savings cost money

Originally borrowed from manufacturing, many firms impose mandatory terms on suppliers, such as payment term or invoice conditions.

Whilst the assertion that this protects the cash-flow position of the company is valid, in many cases the cost of capital is greater to the supplier than the buying organisation. In these instances, it is likely that the purchase price of the goods or services will increase beyond the saving gained, thus creating net negative value.

By examining cost of capital on a sector, product area or even individual supplier basis, buyers can ensure they extract the most overall value from their portfolio, as well as opening up previously excluded corners of the supply base.

Comments